Parkinson’s disease

After a voluntary ten-year break in the transplant of dopamine-producing cells to treat Parkinson’s disease, new trials will now be carried out.

In these trials, five patients in Lund and a further 15 in England and Germany will be treated this year. In one to two years, the effects will be evaluated to decide the fate of transplants.

“We couldn’t just forget the good results we had seen here”, says Håkan Widner, Professor of Neurology at Skåne University Hospital in Lund, who was part of the team that carried out the world’s first transplant of dopamine-producing cells in 1987.

Up to 1999, 18 patients received the surgery in Lund.

“A third of them benefited greatly. All the Parkinson’s symptoms were relieved or eradicated, and the effect was maintained over a long time – up to 20 years. The patients didn’t have to take any medication for Parkinson’s.”

The stop came after two American studies in the early 2000s produced negative results. Some patients saw their condition deteriorate, for example 15 per cent developed more involuntary movements, and the possibility could not be excluded that this was as a result of the transplant.

“We saw nothing like it in our patients”, says Håkan Widner, adding: “What is more, further follow-ups showed that it took longer than expected before the symptom-relieving effects were seen.”

He was not the only one unable to forget the good results obtained in Lund. An international team was formed with the task of closely reviewing the effects of all the transplants carried out. After this, it was decided that it was worth having another go. A comprehensive joint programme was drawn up. The surgery technique itself has been refined, the follow-up of patients after their transplant will be more individualised and the selection of patients will be stricter.

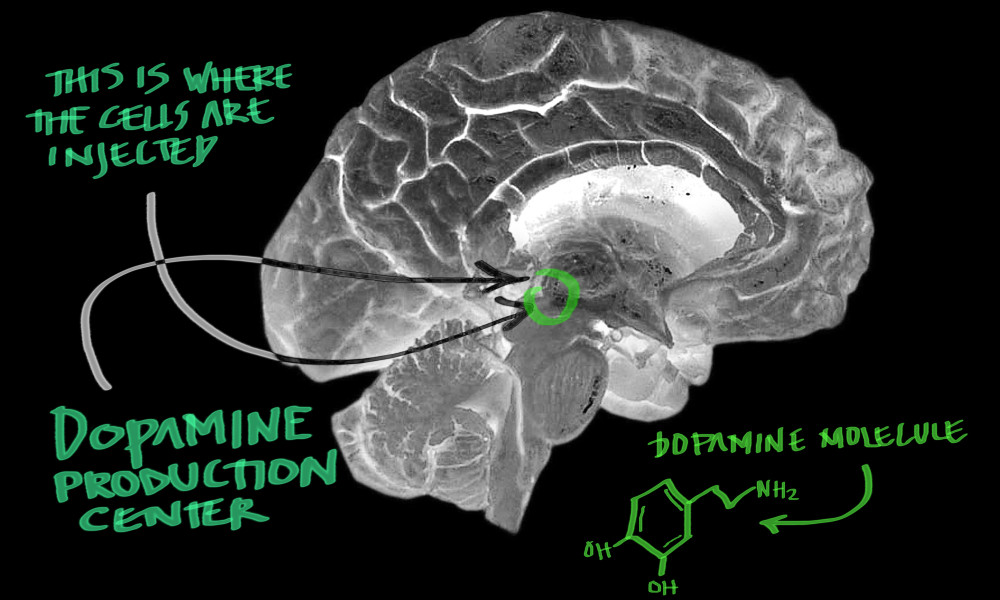

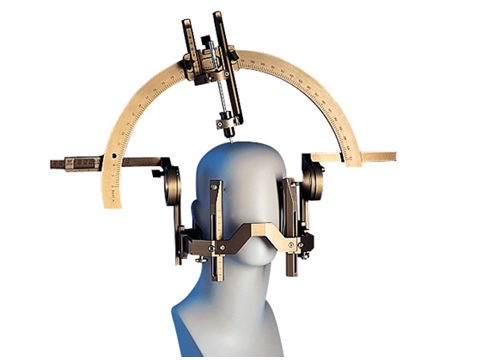

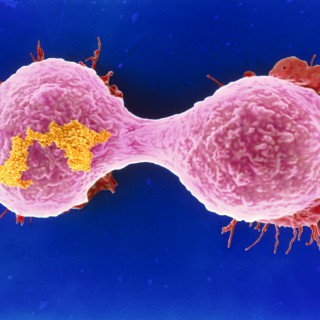

For the operation, a narrow cannula is inserted into exactly the right position in the brain, where the dopamine cells are placed. This is a highly simplified explanation; a transplant entails more than 200 steps, which all have to be carried out in the right order.

A large proportion of the cells, but not all, die before they are able to establish themselves to get nutrients and oxygen.

“A healthy individual has around one million dopamine cells in the brain. We will transplant three to four million cells in each operation”, explains Håkan Widner.

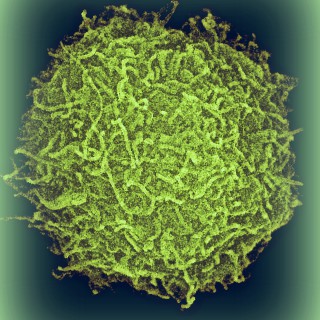

The cells come from aborted foetuses, if the women allow the tissue to be used by the researchers. It is not possible to use cells from adult donors.

“No, unfortunately they die within an hour”, explains Håkan Widner.

The European team, which comprises 15 research groups from five countries, got a name – Transeuro – and a major EU grant of EUR 12 million. The Swedish section is coordinated at Lund University.

Hopes are high for the Transeuro study. If the researchers obtain the results they hope for, transplants could become a reality for other diseases as well in the future, for example Alzheimer’s and Huntington’s disease.

“We have high hopes and expectations for the transplant of dopamine cells.”

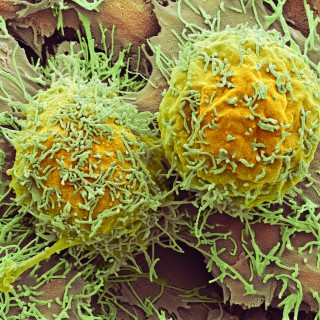

Parkinson’s is the first to be tested because there is extensive knowledge of exactly which cells have been destroyed by the disease and where in the brain the new cells need to be placed.

The patients selected for a transplant must be under 60, have had Parkinson’s disease for no more than ten years and have no involuntary movements. If the transplants succeed, the shaking, stiffness and slow movement that are symptoms of Parkinson’s will be relieved or eradicated.

“We have high hopes and expectations for the transplant of dopamine cells. For a disease that often requires harsh medication, the effects of which also weaken over time, this would be a very attractive solution.”

One problem that remains even if the treatment produces the desired results is the lack of cells to transplant. This cannot become a common method as long as the researchers have to use cells from aborted foetuses.

“We hope that we will be able to use stem cells cultivated in the laboratory in the future. When that day comes, Transeuro will have paved the way for how to carry out the transplants.”

Text: Ingela Björck

Published: 2012