Loss of land depletes the African agricultural production

Agricultural land in Africa is highly relevant for foreign investors and the number of unreported cases of illegal land acquisitions is suspected to be high. “Deals” are not always reported and it can be difficult to find the buyers behind them. Most cases of these acquisitions occur in African countries with food shortages. What is later produced then goes towards exports; food crops that would have been needed in the country.

African agriculture is characterised by its small scale and increased investments are needed. Some argue that large-scale land acquisitions are the answer, but what are the risks?

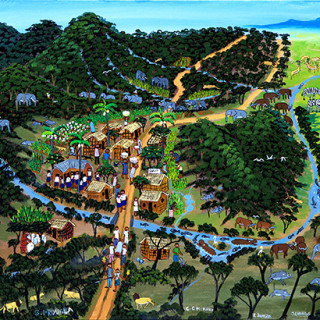

“Large-scale land acquisitions usually involve external private investors, companies and governments purchasing large swaths of land, typically for the cultivation of raw materials to produce biofuels. The same land has for a long time been used by local communities and individuals to produce food and to gather firewood and timber from the forest, and a number of other ecosystem services”, says Yengoh Genesis Tambang, researcher at LUCSUS, Lund University Centre for Sustainability Studies.

The local people are often not aware of the implications such land loss has on their ability to secure their livelihood in the medium and long term; nor are they aware of their rights and how to seek legal redress should any problems arise. This is serious, as it weakens the very basis for agricultural production, productivity and economic development of the countries and regions in question. But there are feasible ways of reaching more fair agreements.

“There are various models that would give local communities more opportunities.”

“There are various models that would give local communities more opportunities to decide for themselves what would be good and profitable for them. One model is that local landowners would become co-investors with their own land in the production of crops and receive returns by being a shareholder in the companies that use their land. Another model, that has been applied somewhat successfully between state companies and local farming communities south of the Sahara, is that the stakes and the profits associated with the cultivation of a product would be divided between landowners and companies. A third model involves more fair land leases, where households receive complete food security”, says Yengoh Genesis Tambang.

Why are women particularly vulnerable in large-scale land acquisitions?

“Women are often responsible for the food production for their families’ consumption. Most agricultural work carried out by men involves the production of crops destined for direct commercialisation, such as palm oil, coffee, and fruit, whereas most women produce food for the household, and can travel long distances in search of opportunities for agricultural land to produce food”, says Yengoh Genesis Tambang.

When land is lost, it can also cause the families to split up. Men leave their villages in search of income opportunities elsewhere, leaving behind the responsibilities of raising children to the women. Some men never return home, leaving women with an even bigger burden.

Women also depend on the money that they make from the sale of surplus food once the family has been cared for. It may be their only source of income, and when they are deprived of that, it tightens the noose. Furthermore, in many cultures, women are not allowed to own land, but they can inherit the rights to cultivate land from their family or through marriage. However, when the land is later leased or sold to companies, the women receive none of the revenues even though they were the ones who first cultivated the land.

Text: Bodil Malmström

Photo: Kennet Ruona