Who do you think you are?

We believe we have direct access to ourselves while we guess or interpret others. But is this really true? Research from the Choice Blindness Lab at Lund University has shown that we know a lot less about ourselves than we think.

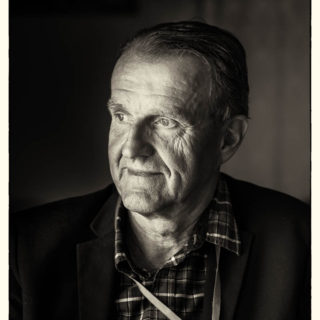

In 2005, Cognitive Scientist Petter Johansson and his research colleague Lars Hall initiated several research experiments, based on well-known “magic tricks”, demonstrating that a free choice is not always free. Their interest in age-old philosophical questions like self-knowledge and free will is what shaped the Choice Blindness Lab.

In one of the experiments, volunteers were asked to look at two pictures of faces, and pick the person who attracted them most. On some occasions, the researchers used a card trick to secretly replace the chosen card with the one that was rejected, and then asked the participants to justify their choice. In 75% of the trials, the respondent had well-formulated opinions on why the chosen face was more attractive than the other – even when the researcher was showing them the wrong picture as having been their choice.

“The experiments pick a hole in our self-image. We don’t know as much about ourselves as we think; rather, our knowledge is an interpretation of our own choices and behaviours. The results of the experiments illustrate how little self-knowledge we have, and demonstrate how easily we can change positions when we argue with ourselves.”

The research is also relevant in areas where we believe we have stronger opinions, such as politics. In another experiment in a park in Malmö, the test subjects were asked to take a stand on some political issues by responding to a survey. After filling in the form, the subjects’ responses were replaced with directly opposite responses (without their knowledge), and they were asked to defend their position.

“This political experiment illustrated the same pattern as we discovered in our previous Choice Blindness studies”, says Petter Johansson. “The test subjects continued to argue in favour of the reversed responses, even though they were the opposite of what the subjects initially thought.”

But why are we so easy to manipulate? Petter Johansson says that we change our views according to our own convenience, and support our own opinions at all times.

“We overestimate the value of our opinions – we think they are good, just because they are our own.. But our opinions, preferences and attitudes are not as firmly rooted as we think, they can unravel if we find ourselves in a situation that requires a different opinion.”

After the experiments, the researchers explained their tricks and the test subjects were greatly surprised that they had argued in favour of the opposing view.

Petter Johansson continues:

“Look at the United States, how the Republicans dance around their own opinions to make them coherent. If Hillary Clinton had done any of the things that Donald Trump is doing now, they would’ve stood up and stomped. But grassroots anger fluctuates, depending on where people believe the information is coming from.”

So what, in fact, makes up the inner core of a human being and what makes up the individual? According to Petter Johansson, this is an open philosophical question that drives his and his colleagues’ research forward through new experiments.

“In all the psychological mechanisms we study, there is always an external limit. Internally, there is a rough texture and certain structures in our behaviour – there’s no doubt about it. And we cannot change all the attitudes and preferences of a human being. If you have devoted your entire life to working for the Palestinian cause, you will not be manipulated into believing otherwise. And since I grew up in Gothenburg and am an IFK Göteborg fan, I would never be fooled into thinking that I support another team. This is simply too big a part of who I am. .”

What have you learned from your research on a personal level?

“That I shouldn’t believe that all my opinions are that strong. In a relationship, knowing that I can always change my mind and take back the things I said provides great comfort. Just because I said or did something five years ago doesn’t mean I need to have the same opinion now. Back then, I probably didn’t even know why I did what I did, and even less so today.

Text: Bodil Malmström

Petter Johansson talks about choice blindness

Facts

-

About Choice blindness