A long walk to freedom

Apartheid, which in Afrikaans means separation, has deep, entangled roots in South Africa. Over the centuries a society was formed with segregation and xenophobia that characterised everyday life.

With his book “Ingen enkelriktad väg till frihet” (No one-way road to freedom), historian Jonas Sjölander wants to discover new layers and see other nuances with regard to Sweden’s sanctions against the industry. How did they affect the South African trade unions’ struggle for democracy?

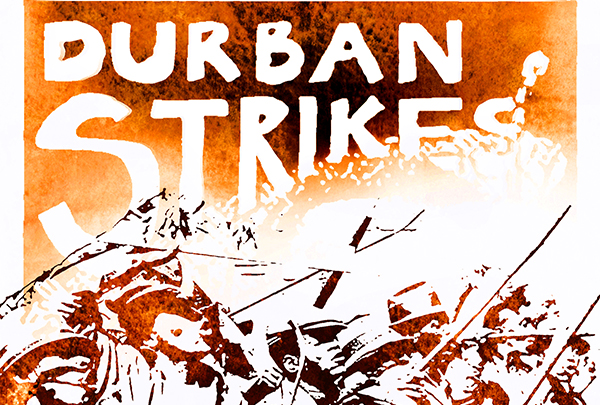

It was the strike wave in Durban in 1973 that got the ball rolling and that would eventually lead to the abolition of apartheid in 1994 with talks of reconciliation and forgiveness. The industry grew in South Africa, and at the same time there was a lack of skilled labour. Previously closed doors were opened for black and so-called coloured people who began to assert their rights. Suddenly, employers could no longer ignore the trade unions’ demands for salary increases because the new emerging skilled workforce was needed. The white working class was not enough. The struggle for better working conditions became a lever to overcome apartheid.

“The strikes in Durban were organised on a grassroots level and their fight was about demands related to the workplace. However, it soon grew into a greater battle about the entire social situation involved in apartheid. Apartheid was no longer productive for the rulers of the country.”

The strikes in Durban with over 100 000 workers paved the way and inspired confidence in other black and coloured workers who wanted to fight for more decent conditions.

International sanctions against the country’s industry played a role, and the black and coloured unions grew strong. Swedish sanctions were the most strict, creating powerful tools to put pressure on companies with the help of IACS, Isolate South Africa Committee. The sanctions also became an effective way to reach out to Swedes to take a stand and form opinions which put pressure on South Africa. However, the sanctions and later the total isolation strategy imposed by Sweden, which after 1986 prohibited new Swedish investments, eliminated jobs and undermined the fight against apartheid.

Meanwhile, international trade unions supported the workers on site by providing training, meeting facilities and moral support.

“The Swedish Metalworkers’ Union was clear not to endorse Sweden’s demands to pull out of South Africa. The union believed that this would inhibit the anti-apartheid movement by eliminating jobs, but there was a paradox. Outwardly, the ANC claimed that the isolation strategy was the way to go, but inwardly they had a different pragmatic approach. On the one hand the isolation of South African industries was effective in forming opinions, and on the other hand, it was the Swedish engineering company SKF’s operations that benefited the South African trade unions. SKF’s culture of negotiation was based on directness and cooperation, and supported the workers’ struggle.”

The Swedish metalworkers’ unions’ counterpart in South Africa, NUMSA, were also sending mixed messages by both wanting to remove multinational companies and then going out on strike when the companies threatened to close.

The situation was and remains complex, and historians like Jonas Sjölander find it hard to grasp the actual truths.

“I think that what happened in Africa has not received a lot of attention in Sweden. We generally talk about our support and what we did. Many Swedish politicians have used our commitment as a trump card, but maybe it was not so crucial, despite being important. It was the trade unions’ movement and the everyday struggle of the South African people that were most important.”

The release of Nelson Mandela in 1994 created massive hopes that South Africa could finally be able to shake its dark history of repression. This was however not to be the case.

More than 20 years since the abolishment of apartheid the gaps are greater and unresolved conflicts persist.

“Black and coloured people are still the poorest, but today we have an inverse quota system that, for certain positions, gives them priority over white people. This has wiped out groups of white people through unemployment, alcoholism and drugs. Certainly there are white people who are active and in favour of an equal society, but there is also a large group of people who are afraid and hide behind walls and guards, and who are prepared to leave the country.”

The trade unions are currently in crisis and the situation became even worse after the brutal massacre in 2012 of miners who went on strike for higher pay in Marikana. 34 were killed, making it the deadliest massacre of its kind since 1994, when South Africa became a democracy.

“The future of South Africa greatly depends on how the ANC, which is closely linked to the state, handles the problems. To continue on the current path suggests a bleak future. South Africa needs to tackle the problem of poverty with better school systems and by slowly building a country that guarantees a certain minimum welfare. We must also combat corruption and bureaucracy. Money gets lost along the way and does not reach people and useful investments.”

Jonas Sjölander is now waiting to receive further research funding to dig deeper into labour migration within the mining industry, and he has already interviewed miners who experienced the massacre in Marikana.

“I love South Africa. It is a wonderful country with wonderful people who are close to rock bottom. Both the darkest and the brightest parts of the spectrum are constantly present. That’s what makes it vibrant.”

Text: Bodil Malmström

Illustration: Catrin Jacobsson

Facts

-

During the apartheid era, four racial categorisations were applied:

-

Black, coloured, Indian/Asian and white.

You were considered part of the category ‘black’ if you belonged to one of the different ethnic groups/tribes/people Xhosa, Zulu, Sotho, Venda, etc. ‘Coloured’ was used for persons of mixed ethnic backgrounds, with roots in Europe, Asia or smaller ethnic groups such as Khoisan or Bantu.

The same four categorisations of South Africa’s population are still used today, but according to individual personal discretion.